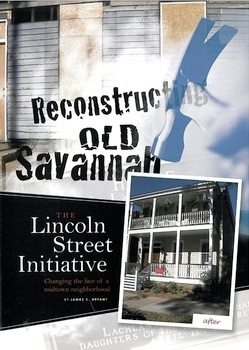

Savannah Magazine - Fall 2007 Homes Issue

"Reconstructing Old Savannah" Featuring SKB Owner, Luke Dickson

Lukejohn Dickson celebrated his birthday admiring a Victorian-era house he has just restored in Savannah’s Thomas Square Streetcar Historic District.

Dickson is passionate about reconstructing neglected and abandoned Victorian-era houses in an economically diverse neighborhood, and he’s planning to restore as many as he can, thanks to a partnership with Historic Savannah Foundation’s Lincoln Street Initiative.

Dickson is not alone in this highly successful venture that began in 2004. Other participants restoring the Lincoln Street neighborhood include some of the city’s well-known builders, preservationists and concerned citizens.

Mark C. McDonald, executive director of Historic Savannah Foundation since 1998, said the Lincoln Street Initiative was the brainchild of the foundation’s board of directors who wanted to promote historic preservation as “a culture of preserving people, property and sense of place.” The initiative was aimed at implementing various preservation techniques and encouraging resident participation while recruiting responsible investment for the ling-neglected community.

McDonald, who frequently lectures on “Saving Savannah’s Architecture,” said the foundation engaged Savannah State University’s urban studies department to examine conditions in the Lincoln Street Neighborhood, which is located between 34th and 31st streets and bordered by Price and Drayton streets. The study analyzed factors such as the crime rate, unemployment, and income levels.

As a result of the study, the HSF board identified a number of historic buildings needing to be rescued, as well as vacant lots where homes had been demolished. Every lot was laid out on a map, and the foundation began acquiring them for resale.

“The idea as to resettle, to repopulate the area, sell the historic buildings to people who would restore them and move into them and make their homes there,” McDonald said. “Our aim is to maintain the economic and ethnic diversity.”

“This year the foundation began the third low-income house on 33rd street inpartnership with Habitat for Humanity director Virginia Brown.

But gentrification is inevitable as a result of the neighborhood’s popularity.

Terry Galloway and her partner, Paula Kreissler, restored a house with a Charleston-style portch on 32nd Street for their residence. Dickson said they did a “masterful” job and took several years to do it.

Mitchell Amidon, an experienced restoration contractor, and his business partner, Andrew Powers, an investor and owner of a local art gallery, recently bought a building at 1704 Lincoln St., the largest building in the neighborhood.

They began an extensive rehabilitation last March, less than 30 days after closing. After restoration of the building, Amidon will have five residential units and a commercial corner. McDonald said the 1912 mixed-use structure is significant as one of few examples of a residential row with a corner store.

The foundation acquired a row house on Lincoln Street a couple of years ago for $90,000 when it was a scarred and boarded-up eyesore. HSF spent $140,000, including a $45,000 grant to re-roof and make it marketable.

“If we hadn’t acquired it, it would be a vacant lot,” he said.

Scott Hinson, a local designer, builder, artist and Savannah College of Art and Design graduate, spent years restoring property on 33rd Street between Lincoln and Abercorn streets. Dickson praises him for taking the “time and patience” to supervise the restoration personally.

Ed Burnsed is another player in the neighborhood. A builder, he constructed new infill in the corridor on 33rd Street. He is restoring a duplex on the corner of 32rd and Lincoln streets, one of his first restoration projects in the Historic District. Doug Kaufman, another builder, recently built two new construction projects on east 32nd and east 33rd streets.

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church on Abercorn Street, which is celebrating its centennial this year, was a forerunner in redeveloping the area.

The Rev. William Willoughby said his church was involved in the restoration of 90 units of housing in the Thomas Square District, the largest piece being the Little Sisters of the Poor Hospital into Sisters Court Apartments at St. Paul’s Place on 37th Street.

The Little Sisters of the Poor, which encompassed the entire square block from Abercorn to Drayton and 37th to 36th streets, was completely restored between 1999 and 2000.

“I believe our pioneer work in the neighborhood set the stage for the present success in redeveloping the area,” he said.

The existing rectory on 34th Street, in the possession of St. Paul’s since 1977, was a bequest of Mrs. J.C. Lewis. “Even though she was a member of First Baptist Church, she left the 1912 house to St. Paul’s to support our ministry in the neighborhood,” Willoughby said. Two years ago it became a resident for the parish priest.

The Lincoln Street Initiative has succeeded in its aim to bring the community together. In the spring of 2006, HGTV (the Home and Garden cable television network) cordoned off Lincoln Street between 33rd and 34th streets for a block party for more than 1,000 people and donated a $45,000 check to McDonald for the Initiative. Private investors attended, as did builders and remodelers and preservationist groups.

A number of individuals and historical preservation groups encouraged the Lincoln Street Initiative by donating money to get restoration under way. The New Jersey-based 1772 Foundation, whose motto is “Preserving American Historical Treasures,” donated $60,000.

“We inherited about $700,000,” McDonald said, “and the board appropriated $150,000 and challenged the staff to come up with a proposal to go to one neighborhood and change the face of that neighborhood.”

McDonald said several board members played key roles in the project, including Board Chair Zelda Tenebaum, Bruce Jacobs, Hugh Golson, Susie Clinard and W. John Mitchell. “In the process, we defined what historic preservation is,” McDonald said.

About 25 buildings have been restored in the neighborhood thus far. “It has been a huge project for us,” McDonald said. “Buying has become difficult for us because it’s such a hot neighborhood right now.” The Lincoln Street is about 80 percent complete.

John Mitchell, former vice president of the foundation, did not restore any of the existing structures, but he bought two vacant lots and constructed infill houses for resale. Others bought condemned buildings and restored them according to strict codes established by the Historic Savannah Foundation and the Metropolitan Planning Commission.

“We purchase property and hold it until we find a buyer,” McDonald said, speaking of the Foundation’s Revolving Fund. Buyers wanting to purchase a property for infill or restoration must first gain approval from the foundation. The Revolving Fund Program is the single most important program the foundation has initiated to preserve endangered buildings through purchase and resale to individuals who will restore them. By reselling, the original donations are recovered and used again on other properties.

The way Dickson sees it, each infill and restoration must have an attachment to the community’s history. “I think the goal of the all preservation is to tell a story about the individual house in its context,” he said. Dickson is restoring his third Victorian-era house in the neighborhood and has several more projects slated for reconstruction.

While the foundation hopes low to moderate-income families will repopulate the community, restoration according to strict guidelines also makes that objective difficult. As Dickson explained, proper restoration is expensive when compared to new construction. He said quality restoration takes a level of expertise and patience.

Builders agree that restoring old structures is probably the most sustainable work they can do, if done properly. Some restoration properties take a couple of years, and some as much as four years. Quality restoration rakes time, and Dickson said the important thing is for buyers and builders to care about quality restoration. “It’s the right thing to do.”

Much of the habitable restoration is happening among quality builders. Not surprisingly, there is a market for restored homes in the neighborhood. Many younger people are opting for urban living in the Historic District. The revitalization program is attracting a new generation of city dwellers who like being part of the historic community.

People are living and working in the Lincoln Street Neighborhood. Dickson said one of the goals of the initiative is “not to recreate the community but to reintroduce something. This is exciting, especially for my generation.”

Although quality period restoration benefits the homeowner and investor, it is more demanding and expensive than infill construction for rental properties. A few observers are critical of some infill projects. Some projects turn out better than others. Dickson said when buyers do not use trained architects and designers to consult with the preservation organizations like the Historic Savannah foundation, the results are disappointing and frustrate the aims of the initiative.

“Buyers and builders have to be willing to participate in the proper design process with the foundation,” Dickson said. “It is important to maintain the integrity of the building so that owners down the line have the house as originally designed.”

The Lincoln Street Initiative is a compelling example of one historic neighborhood’s return after years of neglect. It has become a model for urban living in a diverse population with neighborhood shops and stores and secluded neighborhood street enclaves. Best of all, it is excellent proof of what can happen when a community works together.

The foundation acquired a row house on Lincoln Street a couple of years ago for $90,000 when it was a scarred and boarded-up eyesore. HSF spent $140,000, including a $45,000 grant to re-roof and make it marketable.

“If we hadn’t acquired it, it would be a vacant lot,” he said.

Scott Hinson, a local designer, builder, artist and Savannah College of Art and Design graduate, spent years restoring property on 33rd Street between Lincoln and Abercorn streets. Dickson praises him for taking the “time and patience” to supervise the restoration personally.

Ed Burnsed is another player in the neighborhood. A builder, he constructed new infill in the corridor on 33rd Street. He is restoring a duplex on the corner of 32rd and Lincoln streets, one of his first restoration projects in the Historic District. Doug Kaufman, another builder, recently built two new construction projects on east 32nd and east 33rd streets.

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church on Abercorn Street, which is celebrating its centennial this year, was a forerunner in redeveloping the area.

The Rev. William Willoughby said his church was involved in the restoration of 90 units of housing in the Thomas Square District, the largest piece being the Little Sisters of the Poor Hospital into Sisters Court Apartments at St. Paul’s Place on 37th Street.

The Little Sisters of the Poor, which encompassed the entire square block from Abercorn to Drayton and 37th to 36th streets, was completely restored between 1999 and 2000.

“I believe our pioneer work in the neighborhood set the stage for the present success in redeveloping the area,” he said.

The existing rectory on 34th Street, in the possession of St. Paul’s since 1977, was a bequest of Mrs. J.C. Lewis. “Even though she was a member of First Baptist Church, she left the 1912 house to St. Paul’s to support our ministry in the neighborhood,” Willoughby said. Two years ago it became a resident for the parish priest.

The Lincoln Street Initiative has succeeded in its aim to bring the community together. In the spring of 2006, HGTV (the Home and Garden cable television network) cordoned off Lincoln Street between 33rd and 34th streets for a block party for more than 1,000 people and donated a $45,000 check to McDonald for the Initiative. Private investors attended, as did builders and remodelers and preservationist groups.

A number of individuals and historical preservation groups encouraged the Lincoln Street Initiative by donating money to get restoration under way. The New Jersey-based 1772 Foundation, whose motto is “Preserving American Historical Treasures,” donated $60,000.

“We inherited about $700,000,” McDonald said, “and the board appropriated $150,000 and challenged the staff to come up with a proposal to go to one neighborhood and change the face of that neighborhood.”

McDonald said several board members played key roles in the project, including Board Chair Zelda Tenebaum, Bruce Jacobs, Hugh Golson, Susie Clinard and W. John Mitchell. “In the process, we defined what historic preservation is,” McDonald said.

About 25 buildings have been restored in the neighborhood thus far. “It has been a huge project for us,” McDonald said. “Buying has become difficult for us because it’s such a hot neighborhood right now.” The Lincoln Street is about 80 percent complete.

John Mitchell, former vice president of the foundation, did not restore any of the existing structures, but he bought two vacant lots and constructed infill houses for resale. Others bought condemned buildings and restored them according to strict codes established by the Historic Savannah Foundation and the Metropolitan Planning Commission.

“We purchase property and hold it until we find a buyer,” McDonald said, speaking of the Foundation’s Revolving Fund. Buyers wanting to purchase a property for infill or restoration must first gain approval from the foundation. The Revolving Fund Program is the single most important program the foundation has initiated to preserve endangered buildings through purchase and resale to individuals who will restore them. By reselling, the original donations are recovered and used again on other properties.

The way Dickson sees it, each infill and restoration must have an attachment to the community’s history. “I think the goal of the all preservation is to tell a story about the individual house in its context,” he said. Dickson is restoring his third Victorian-era house in the neighborhood and has several more projects slated for reconstruction.

While the foundation hopes low to moderate-income families will repopulate the community, restoration according to strict guidelines also makes that objective difficult. As Dickson explained, proper restoration is expensive when compared to new construction. He said quality restoration takes a level of expertise and patience.

Builders agree that restoring old structures is probably the most sustainable work they can do, if done properly. Some restoration properties take a couple of years, and some as much as four years. Quality restoration rakes time, and Dickson said the important thing is for buyers and builders to care about quality restoration. “It’s the right thing to do.”

Much of the habitable restoration is happening among quality builders. Not surprisingly, there is a market for restored homes in the neighborhood. Many younger people are opting for urban living in the Historic District. The revitalization program is attracting a new generation of city dwellers who like being part of the historic community.

People are living and working in the Lincoln Street Neighborhood. Dickson said one of the goals of the initiative is “not to recreate the community but to reintroduce something. This is exciting, especially for my generation.”

Although quality period restoration benefits the homeowner and investor, it is more demanding and expensive than infill construction for rental properties. A few observers are critical of some infill projects. Some projects turn out better than others. Dickson said when buyers do not use trained architects and designers to consult with the preservation organizations like the Historic Savannah foundation, the results are disappointing and frustrate the aims of the initiative.

“Buyers and builders have to be willing to participate in the proper design process with the foundation,” Dickson said. “It is important to maintain the integrity of the building so that owners down the line have the house as originally designed.”

The Lincoln Street Initiative is a compelling example of one historic neighborhood’s return after years of neglect. It has become a model for urban living in a diverse population with neighborhood shops and stores and secluded neighborhood street enclaves. Best of all, it is excellent proof of what can happen when a community works together.